Keil Space: detecting Universe in art with astronomer Massimo Tarenghi

Astronomer and professor of astrophysics finds the cosmos in Keil Space’s artistic experience

Astronomer and Full Professor of Astrophysics in the University of Milan, Massimo Tarenghi worked at the Steward Observatory in Arizona and the European Southern Observatory (ESO) as an international staff member, where he directed the design of the first active-optics telescope ever created, the New Technology Telescope, and that of the Very Large Telescope in Chile, the world’s most advanced optical instrument. The scientist directed the Cilean Paranal Observatory, as a representative of ESO, for which he is now astronomer emeritus. He was also director of Atacama Large Millimeter Array, the most important radio astronomy station ever built. A member of the Accademia dei Lincei for more than 20 years, he was appointed Commendatore della Repubblica Italiana, the highest of the Republic’s orders. He was also awarded Chilean nationality for his contributions to the development of astronomy. Tarenghi ranges in his scientific research between galaxy clusters, large-scale matter distribution and active galactic nuclei.

Professor Tarenghi visited Keil Space, a place that holds Samantha Keil’s Advanced Art Exhibition. The scientist’s impression of Keil’s artistic research gives us a whole new perspective on our presence in the galaxy and how observing can position us into reality.

The entrance is immediately familiar to the Professor, who says he had the same experience with the one they created at their observatory in Chile. A ramp that enters underground and, as the doors open, manifests a completely different environment. From the Chilean desert to the underground research laboratory, from the chaotic Florence crowded with tourists, to the silent and solitary art space, with “the stillness and beauty of simplicity.” A space, says Tarenghi, with “simple elements placed in critical points that attract your gaze and your interiority at the same time” thanks to what results as a place of peace.

Muscle tension toward the stars

From his encounter with the First Generation of Bronzes, the astrophysicist recognizes common elements among the sculptures on display, each with its own singularities. Prominent among them all is Lovers, central in the room, in which a tension toward the heavens is recognized. The tensive dynamic in the perception of the bronze subjects is pervasive. The “force of muscles and position” propels the two figures upward, preparing them for the complexity revealed by the viewer’s movement around the bodies. Tarenghi underlines that he would spend hours exploring the details and complexity of the subjects with exposed, skinless muscles, trying to grasp the power of momentum in tension toward the cosmos.

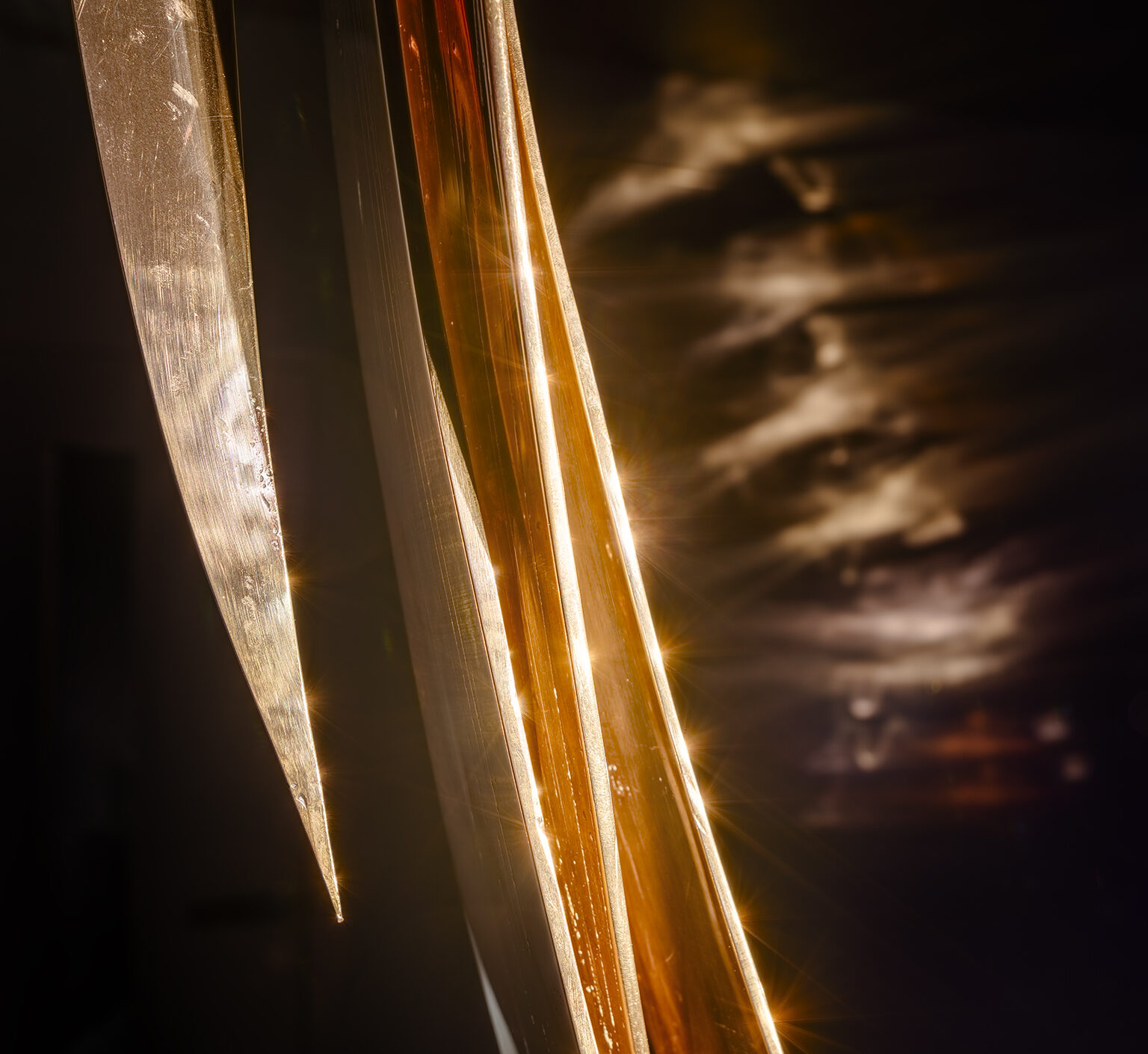

Light at the origin of the Universe

Light can evoke an unlimited amount of meaning; it takes us back to the origins of meaning as to that of the world. It is through light that the Second Generation of Bronzes brings its message, its zenithal view of matter. The illumination guides and is guided by the observer, Tarenghi recounts that “you see two elements tending to the same point, then you turn around and see the illumination with various points of light that move as soon as you move. That’s where I found key elements also present in the CERN high-energy particle accelerator.” The professor finds in Sabre, central work of the Second Generation, inferences and references to the two colliding beams of protons that for a few moments recreate the matter present at the origin of the universe. “Maybe you can see the opposite, the Big Bang creating the whole expanding universe” the professor speculates, recalling the experience of being present in front of the bronze struck by light. In particular, the visitor’s wonder is aroused by the precise scientific reference and the simplicity with which Samantha Keil evokes the birth of matter as we know it.

At the center of our galaxy

With the New Generation of Bronzes, facing the depths peering into the individual, the astrophysicist finds a poetic commonality among “all things” in existence. “The universe is more unified than we think” he states, bringing a universal gaze to the existence of matter. “A portion of bronze and a galaxy appear almost identical, how is that possible?” According to the scholar, this is the manifestation of all matter we know, all belonging to the same universe. Entering the room of the multisensorial experience, Tarenghi admits that he wants to be alone from the beginning, he feels like a call to solitude due to the need to absorb all the energy released by the work. “And you don’t want to share it with anybody because it’s an energy that comes from outside to you and complements your energy. In a way it’s like being in a desert observing the Milky Way wanting to be alone, wanting to feel it as your own. So being alone is like saying: this is part of me.” In this reflection on himself and the universe that the observer finds himself, facing the figures that emerge spontaneously from looking closely at bronze, at matter, at the unconscious.

The observer’s journey is focused precisely on interiority. “It is the most accurate way to go to the center of our galaxy, the famous Sagittarius. I did my physics thesis on this 50 years ago.” This way the professor discovered that there are black holes at the center of the galaxy, where everything is “transformed, amalgamated, everything shifts, everything changes.” The experience brings the visitor close to the point in our galaxy where bodies, animals, structures are forming, in an interpretive parallel with perception and the search for forms in the undefined. Undefined as in a black hole, as in the formation of meaning from perception and the unconscious. In fact, Tarenghi states, “the longer you stand there, the more you see new things forming,” inviting anyone to appreciate that feeling even for an hour, percieving the imaginative potential in observing and creating new figures of the world.

Keil’s fundamental contribution to the construction of this view of the universe lies precisely in the simplicity with which the artist proposes looking at complexity, the astrophysicist says, “and this is fundamental to the work of the scientist.” At Keil Space “the immense and the microscopic are the same thing, both dimensions are expressions of the universe.” Matter, according to Tarenghi, is simply and precisely represented in Samantha Keil’s work, feeling a common essence among all the elements of the cosmos, tending to the introspection of ourselves and the universe we inhabit.

“Art is not made for large visiting groups. Art is me and the work.”

Of the utmost importance to the scholar is the ability to “be part of the art world not only by observing, but also by integrating oneself with the work.” And this is what he perceived in his visit to Keil Space. The contrast to the usual: the chaotic experience prevalent in museums in Florence, where it becomes almost impossible to be alone in front of art. Tarenghi presents the visit as “meeting the artist through meeting oneself in art,” and it is with hope for more space, more spaces of this encounter, that he leaves a word of tank to artist Samantha Keil and ends his “sensory experience of beauty and depth.”

We deeply thank Professor Massimo Tarenghi for his precious reflection and invite the readers to watch the full interview at this link.